Space Oddities

Space Oddities: UWG Art Professors Get Creative with Lunar ProjectShare this page

Mark Schoon and Casey McGuire are not only associate professors of photography and sculpture, respectively. Together, they hold the distinction of being the only members of the University of West Georgia community to have walked on the moon.

Well, sort of.

In a far corner of the Visual Arts Building on campus, Schoon and McGuire play in their lunar sandbox, experimenting with materials while working on a collaborative project that has been evolving since 2015.

The project –“The Great Moon Hoax: Science and the Recreation of the Artificial” – was influenced by a series of images and articles that ran in the New York Sun in 1835. In that series, astronomer Sir John Herschel was credited for discovering life on the moon while gazing through his telescope on expedition to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa.

The reality, although exciting for the early 19th century, wasn’t nearly as sensational. There was no evidence of bat-men, unicorns or massive craters with enormous amethyst crystals.

“The photograph Herschel took of the moon wasn’t really of the moon,” McGuire explained. “It was of a sculpture he made after looking through the telescope, trying to create what he was seeing so he could show people what it looked like. It wasn’t a creative act or statement – it was scientific.”

Schoon approached McGuire with a desire to recreate the Copernicus crater, a lunar crater Herschel modeled in 1842. They began with plaster, then added materials to it, like fish tank rocks. The lighting and photography process that followed helped them determine what would work and what required them to go back to the drawing board.

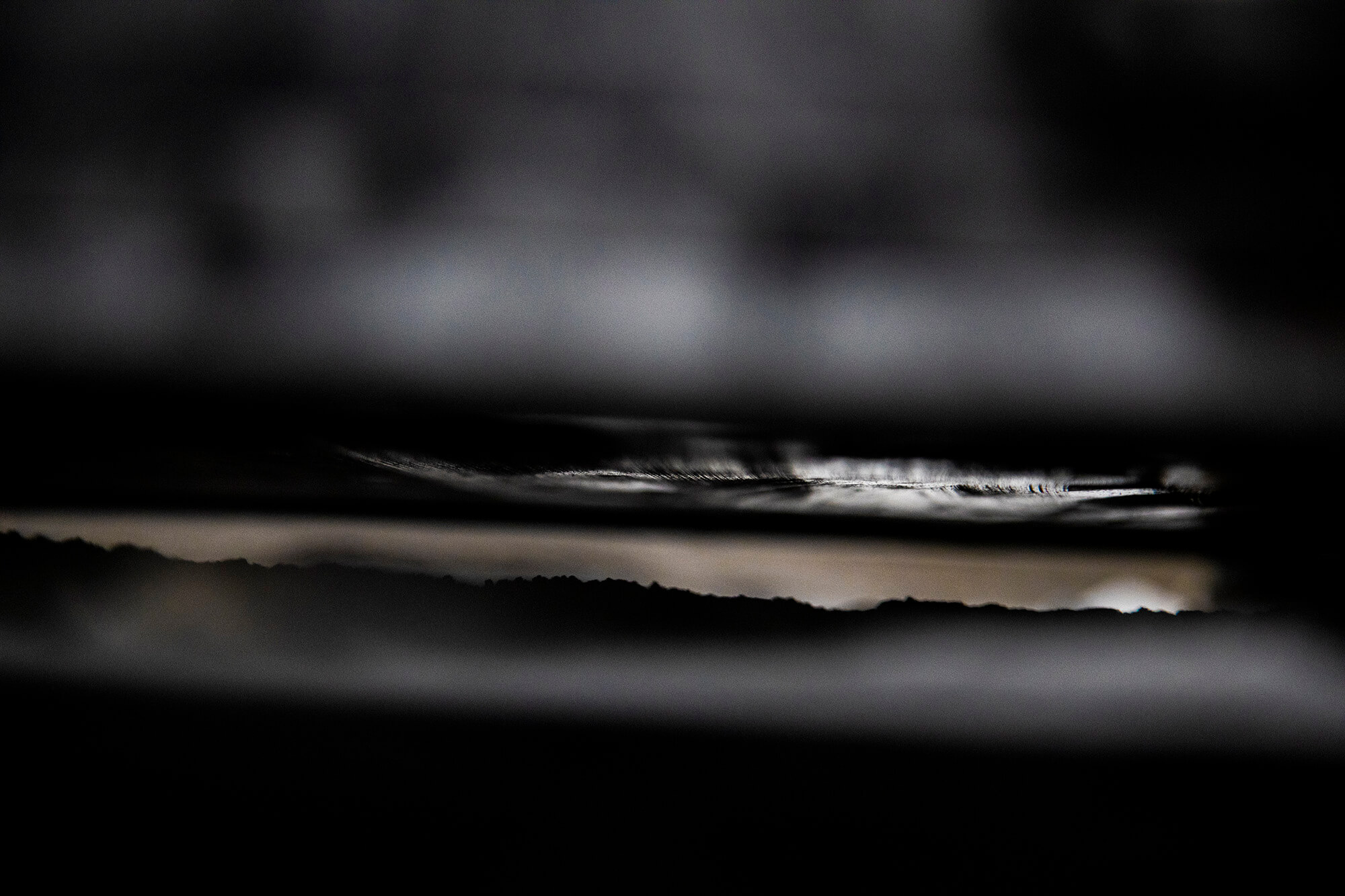

“Some of the very first images were created because I was casting concrete countertops and the loose concrete fell into a bucket,” McGuire recalled. “It pitted and looked like the moon, so I knew I had to get a photo of that.”

The pair purchased more concrete to play with and made other discoveries. Once the concrete hardened, they were able to pick it up, but if they hit it from the air compressor it fell apart because it was being held together with humidity.

“These acts of playing with the material are what lead to a lot of the outcomes we had,” McGuire continued. “Mark would observe, ‘That held together, and it kind of looks like Rosetta’s comet.’ That is where the most successful work happens – it’s just that simple.”

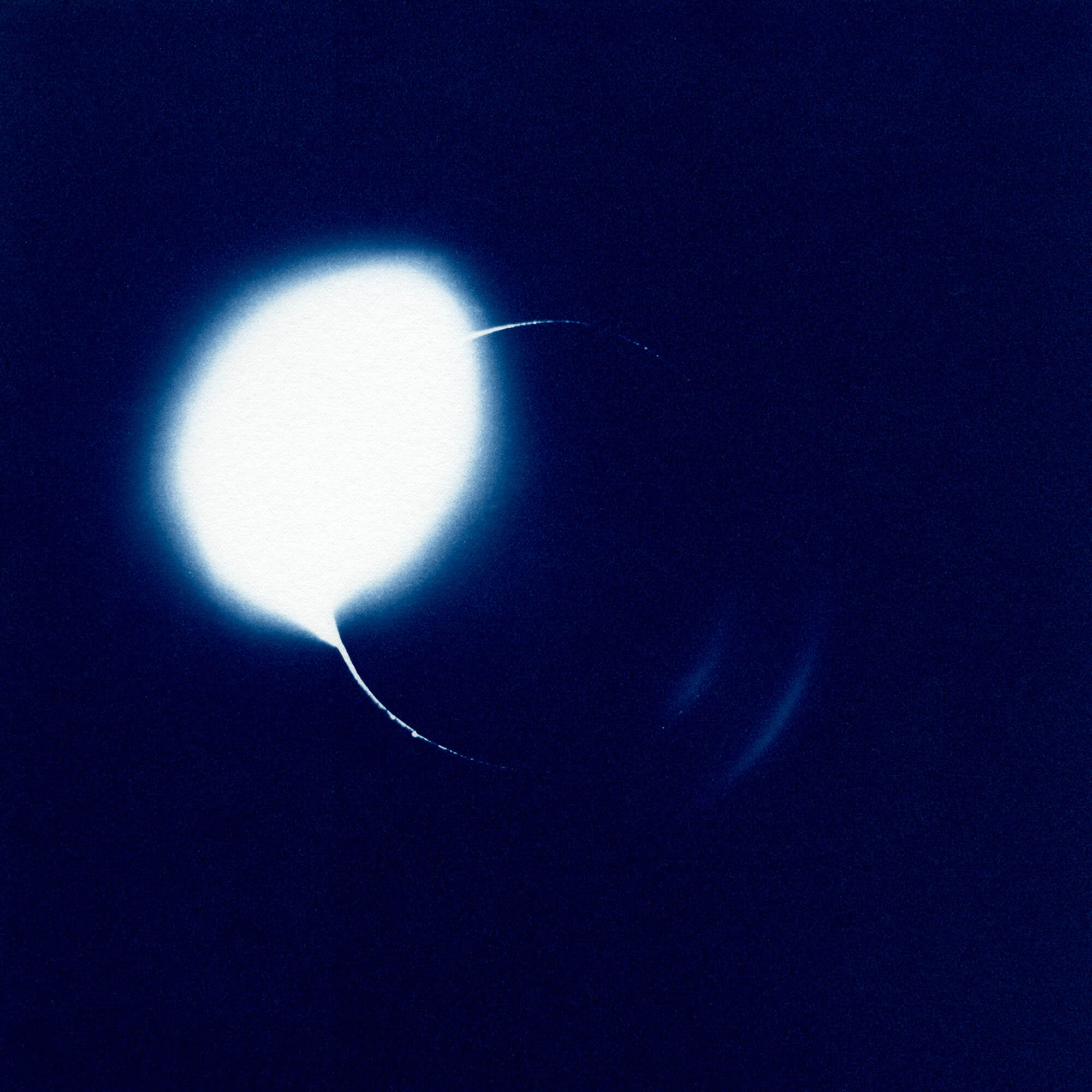

When casting for the planets, McGuire would string cocktail ice balls, dip them in water and hang them up to photograph. She continued to experiment by putting different colors and reflective objects in the ice balls, including glitter.

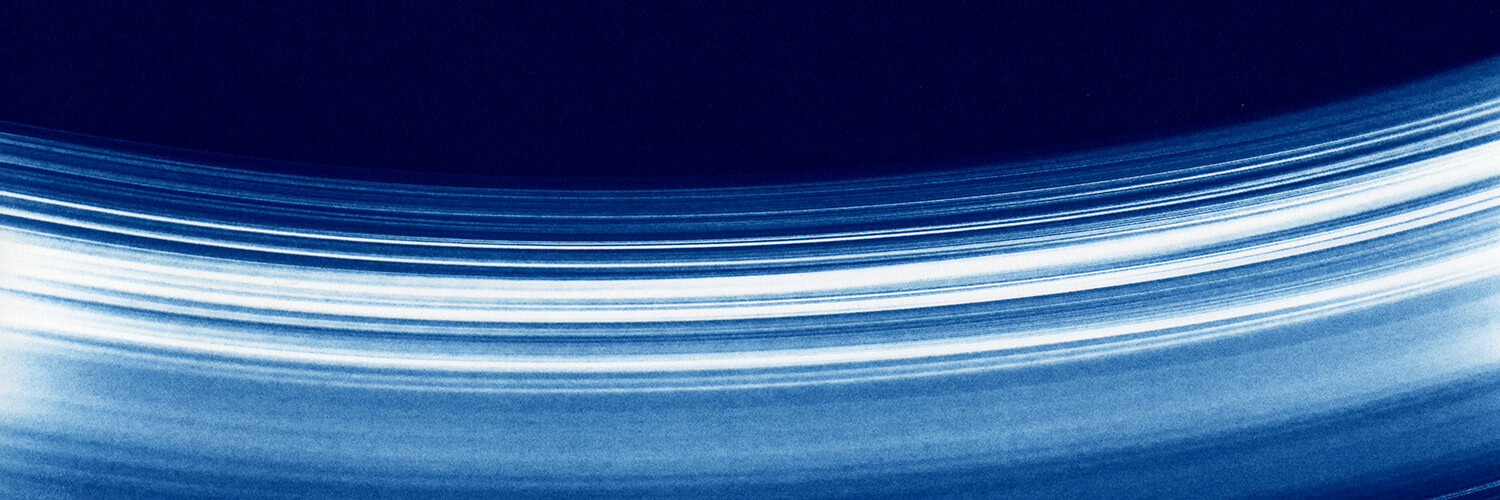

“Because the different pieces of glitter reflected the light, it totally changed the way the ice ball appeared when we slowed the shutter speed down and took a photo,” McGuire observed. “Then swinging the ball made the lines look like Saturn’s rings.”

“At the beginning, we didn’t know if these were going to be a series of sculptures and photographs or what. It turns out we’re making things that now can only exist as photographs. You never know; you just have to be open to the possibilities.”

The aspect of play is important, especially when talking about research, Schoon said.

“It’s something that gets diminished in the academic process in which you are just so focused on doing certain things for certain goals, toward certain outcomes, for certain people,” he explained. “Even though we have goals, when we go into the studio everything is a game. We would let it lead us.”

Although the project is not new, Schoon said the pair’s partnership allows for a constant push and pull that keeps ideas fresh.

“The pull allows one of us to slow down and observe,” he explained. “Those are the kinds of things that don’t happen when you are working by yourself. You might be conscious that you need to do that, but it is hard to just pause for a second and see what’s happening and if it’s of value or not.”

But it’s not all fun and games.

But it’s not all fun and games.

When it came to printing, they decided to once again take direction from the past.

“Right along the same time Herschel was making important observations of the universe, he was helping to invent photography and making some of the earliest photographs,” Schoon said. “He invented this process called the cyanotype, which we thought we should try and create along with salt prints.”

Cyanotype is a photographic printing process that produces a cyan-blue print, which was later referred to as blueprints. The salt print is a paper-based photographic process for producing prints from negatives.

“The technical part of making the salt prints is definitely the most challenging,” Schoon said. “It is a process that neither of us had done before – very finicky and very problematic. They are antiquated for a reason.”

Because of this, McGuire said they may have 15 prints for every one salt print.

“You hand paint the silver nitrate onto the sheet of paper in the dark, and you can’t see whether you have coated the whole thing or not so you have to be very meticulous about it,” she explained. “We want these to be really well-crafted, very tight and perfect prints because that gives way to the conversation about the truth in the image. If you see big brush strokes of the silver nitrate through the print, that is going to detract from the reality we are trying to create.”

“You hand paint the silver nitrate onto the sheet of paper in the dark, and you can’t see whether you have coated the whole thing or not so you have to be very meticulous about it,” she explained. “We want these to be really well-crafted, very tight and perfect prints because that gives way to the conversation about the truth in the image. If you see big brush strokes of the silver nitrate through the print, that is going to detract from the reality we are trying to create.”

Space is also a challenge. Because they do not have a large enough exposure bed, the cyanotypes and salt prints have to be exposed in the sun.

“If it’s not sunny on one of the days we work in the studio, we can’t print,” McGuire confessed. “We keep exceeding size and scale in different ways. For example, the diorama we use in my studio is a four-by-eight sheet of plywood against another four-by-eight sheet of plywood with a metal arm with which we can hang items. We keep running into growth problems.”

Schoon described the patience that has accompanied this project as unique.

“It’s been four-and-a-half years, and we are still making work, which is remarkable,” he observed. “If I had been working on another photography project for this long, typically I’d have five times the number of images, or I'd have multiple projects. But with ‘The Great Moon Hoax,’ we have 25-30 images we’ve made, which, in photography, isn’t that much.”

Schoon and McGuire have hit the road with “The Great Moon Hoax” nine times in cities ranging from Atlanta to Chicago and New York to Los Angeles. That’s in addition to work as full-time professors.

“One thing that surprised me as the project developed was that it reinforced so many of the things I do in the classroom,” Schoon recognized. “The ideas and the critical thought and theory of photography that I try to talk to the students about is evident in this project. It bridges this gap between the historical aspect of photography and contemporary concerns and holds them together.”

It is also important to emphasize there is a visual to accompany every story.

It is also important to emphasize there is a visual to accompany every story.

“Every time there is a discovery in space, if there isn’t already a picture, they make one for it,” Schoon explained. “In the art department, sometimes students get so discipline-specific, but being an artist is figuring out a solution to what you want to make. At the beginning of this project, we didn’t know if these were going to be a series of sculptures and photographs or what. It turns out we’re making things that now can only exist as photographs. You never know; you just have to be open to the possibilities.”

McGuire said she catalogues different imagines of in the back of her mind, saving them for future ideas.

“Recently I bought a little moon rover toy and models of space stations,” she concluded. “I bought a bunch of emergency foil blankets, and we talked about using that in an image. People might not notice it, but we do. There are all these materials in the world around us that we can edit in a closure photo and change it. Everything is possible.”